Bavarian Beer: A Unique Blend of Tradition and Technology

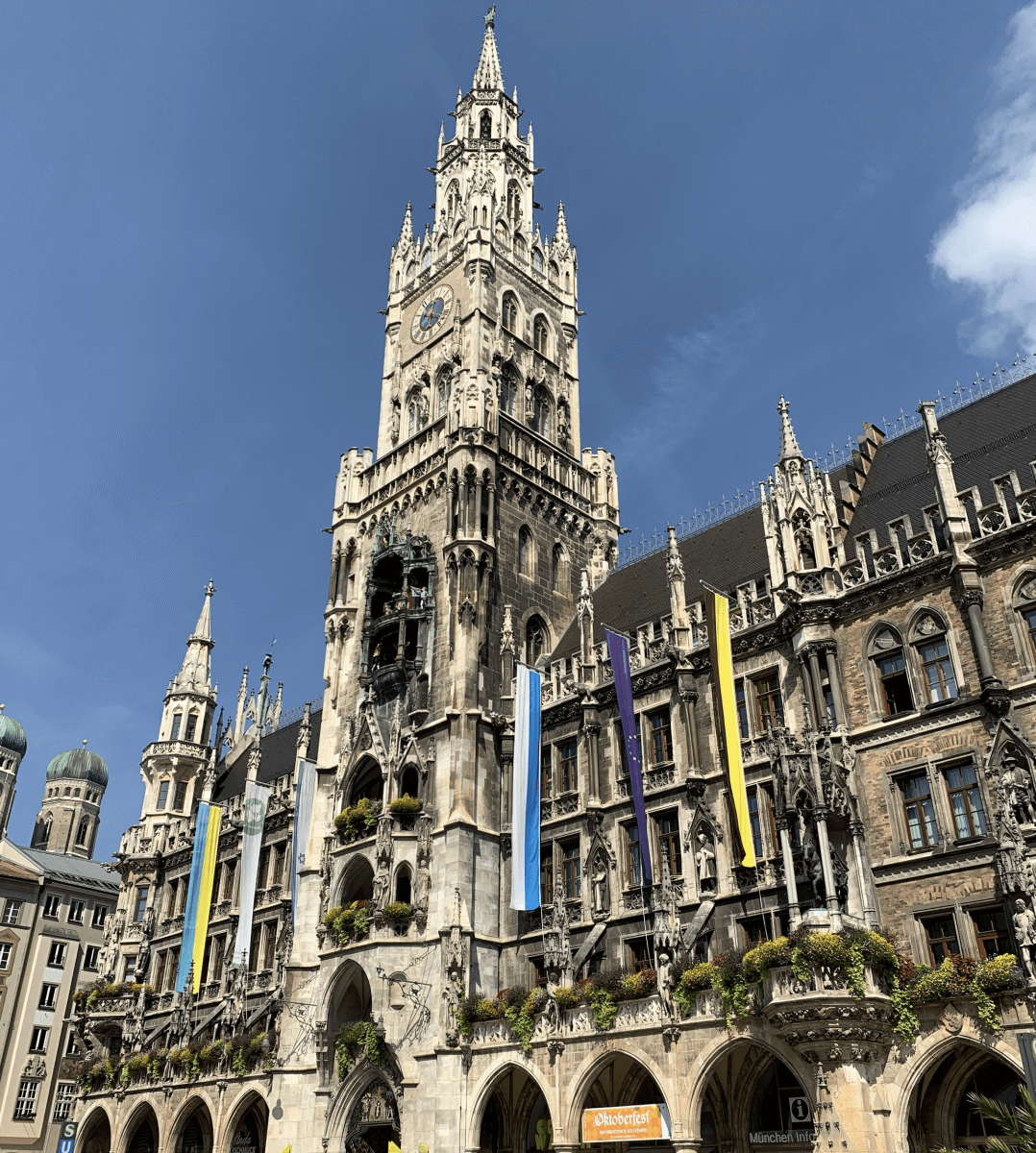

The Glockenspiel at Marienplatz

It’s early afternoon on September 2, 2024, and the weather is beautiful. I’m sitting in the biergarten of the 435-year old Hofbrauhaus in Munich, at a table with six older German ladies. It is so busy here that they’ve asked if they can share my table for their birthday celebration, which actually worked in my favor because my German ist nicht sehr gut. They know how to get things ordered here and they’ve flagged down the waiter (30 minutes after I initially waved him over) and have ordered for our table. They’re shocked that I’ve asked for a Dunkel, because it’s so dark! But they’re almost more shocked at how I’m holding my Mass mug. I’m holding it by the handle, and they show me that I need to put my hand through the handle and wrap it around the glass. “But, won’t my hand make the beer warm?” They sort of shrug and say “it’s tradition!” and obviously looking like a tourist is much worse than having a potentially warm beer.

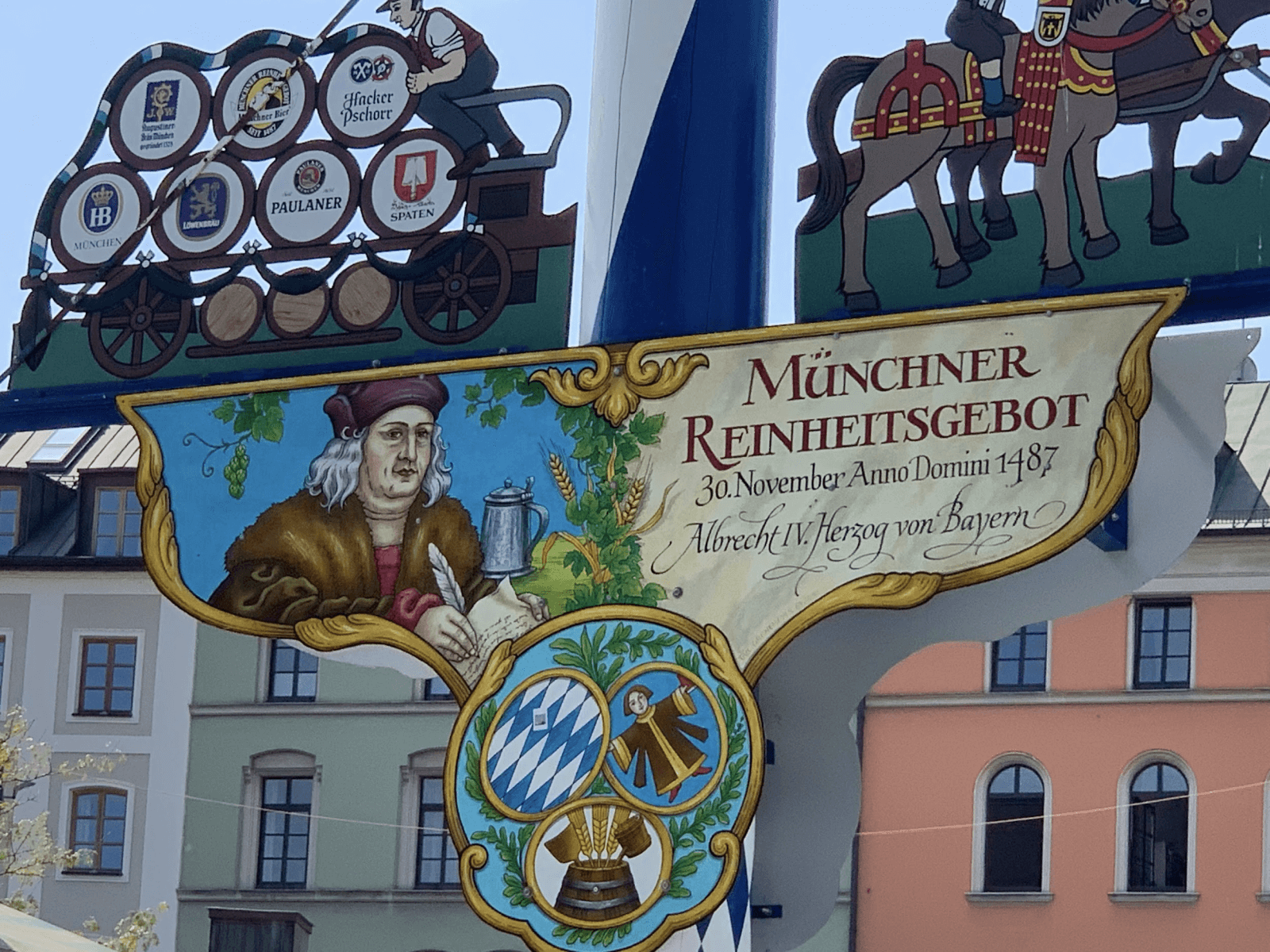

You might have guessed by now that beer, and rules, and tradition are extremely important to Germans, especially Bavarians. Bavaria is a large state in southeastern Germany which borders Austria and the Czech Republic. To most people, Bavaria means Neuschwanstein Castle, the Glockenspiel, conservative values, the birthplace of the Nazi Party, and brass oompah bands. If you work in the beer industry, or are even just a beer fan, to you Bavaria means Oktoberfest, Weyermann Malting, Bamberg and Schlenkerla and rauchbier, Munich helles and Munich dunkel, and hop fields as far as the eye can see. Munich, (or München), is the capital of Bavaria, and beer is taken more seriously here than the rest of Germany. Most people have heard of the Reinheitsgebot, which is the German Purity Law of 1516; this law very specifically details how beer can be produced if it wants to have the purity label on it. However, what many people don’t know is that it was originally the Bavarian Purity Law of 1487 (Münchner Reinheitsgebot), and Bavaria would not join a unified Germany unless the rest of the country adopted these rules. The Bavarians do not joke about their beer.

Maypole representing the Munich Reinheitsgebot and Munich Brewer’s Guild at the Viktualienmarkt

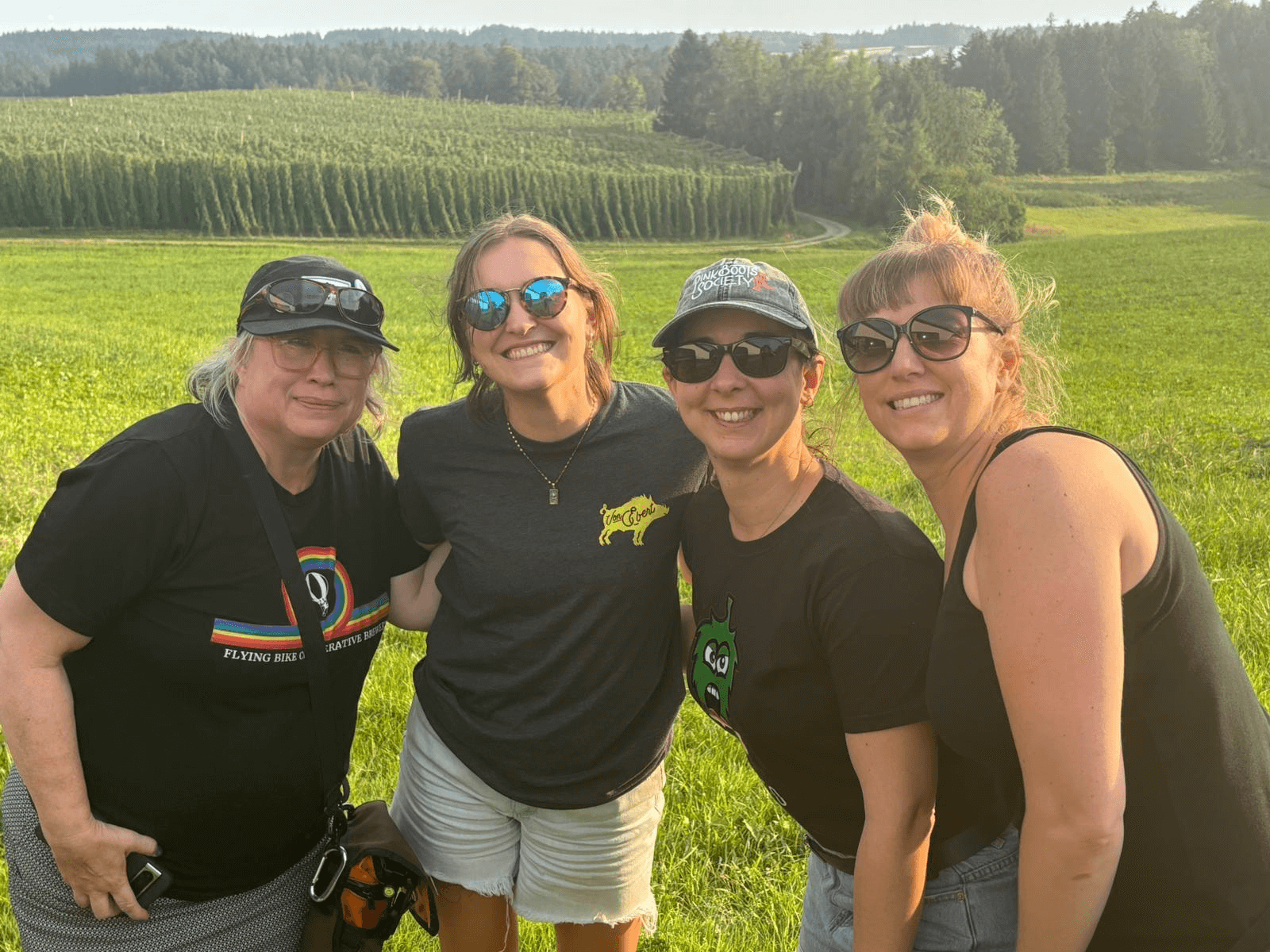

I have made my way to Munich for what I am expecting to be the experience of a lifetime. (Our tour guide’s name is Trip; would you expect any less?) I’m joining three other female brewers (and a dude named Brad) for a tour of the hop growing regions in Bavaria. I’d been a Pink Boots Society member for four years at this point and one thing that I love about the organization is their scholarships. There’s such a wide variety of offerings; in-person experiences, virtual courses, curated book packs, business planning assistance, and so on. There are scholarships offered each quarter throughout the year and the application process is fairly simple; fill out the online questionnaire, submit an essay, and include an optional letter of recommendation. Applications are reviewed by a committee, but they do not know whose materials they are reviewing. I’ve been told throughout my life that I’m a fairly decent writer, so I feel like my essay was good enough, but even now, five months later, I’m still shocked that I was awarded this scholarship. I also believe that having a letter of recommendation is extremely helpful, so I have to thank one of my beer mentors, Annette May, for submitting a letter to support my application.

Two years ago, I was also lucky enough to be awarded a travel scholarship from my chapter (Canada) to attend the Hop and Brew School in Yakima, put on by Yakima Chief Hops. I absolutely love hops. As brewers, I believe that we all have our favorite ingredient. Mine is hops. I got pulled into craft beer many years ago after trying my first Bell’s Two Hearted (Centennial single hop), and once I began brewing, opening that bag of hops and taking a deep inhale was often the best part of the day. Planning out my hop schedule and researching hop varieties was what I did for fun in my free time. I am also becoming more aware that as I age, my body just doesn’t Iike doing physical labor all day. What else can I do then? Of course the first thing that came to mind was working in the hop industry somehow. After having been to Yakima, the hop capital of the US, I was excited and eager to see how the hop industry functions in the hop capital of Germany. (And clearly next on my list is a hop tour in New Zealand). So this is how I found myself in Munich, anxiously awaiting the start of this great beer and hop tour.

The four of us scholarship recipients meet up the night before our tour begins in the Werksviertel area of east Munich. Two of our group came from the United States, one from Australia, and me from Canada. One thing I appreciate about opportunities like this is the chance to meet other women and talk abou brewing and what it’s like where we each live. The networking and friendship that come from these scholarships is absolutely unparalleled. I also find it helpful because our brains think differently, and so we ask different questions and gain different insights from each experience, which means that we are learning from one another in addition to learning from our tour guides. The next morning, September 3rd, we connect with Trip Kloser (and Brad), and we are off.

Trip has planned this week long excursion out to a tee. To many tees actually. We have a very full schedule, and what we learn pretty quickly is that we aren’t just taking regular run of the grist mill tours and talking to average everyday tour guides. We’re going deep into the basements of some of the oldest breweries in the world. We’re owing to see the control rooms and technology that’s now commonplace at these large scale operations. We’re having intimate lunches and dinners with the brewmasters and production managers and executive level personnel. We’re meeting the farmers and lab managers and the hop geneticists and the farmer’s grandma. (Unfortunately, we didn’t get to meet any of the hopfenkönigen, or hop queens). Every single meeting involves beer tasting, sometimes with beer from a large brewery, sometimes something experimental, sometimes someone dips into their cellar and we’re drinking things that are super rare, have been aging for a decade, or may never be commercially released because they come from someone’s home brewery. It’s overwhelming but at the same time we quickly settle into a routine of get up early, be prepared to start beer tasting before lunch time, eat lots of carbs and cheese, do lots of walking and stair climbing (which sort of offsets the beer and food), all while we surround ourselves with Bavarian culture and history. This is what we do, jeden tag, for a week. It’s very apparent that Trip knows everybody, and we could not have a better guide.

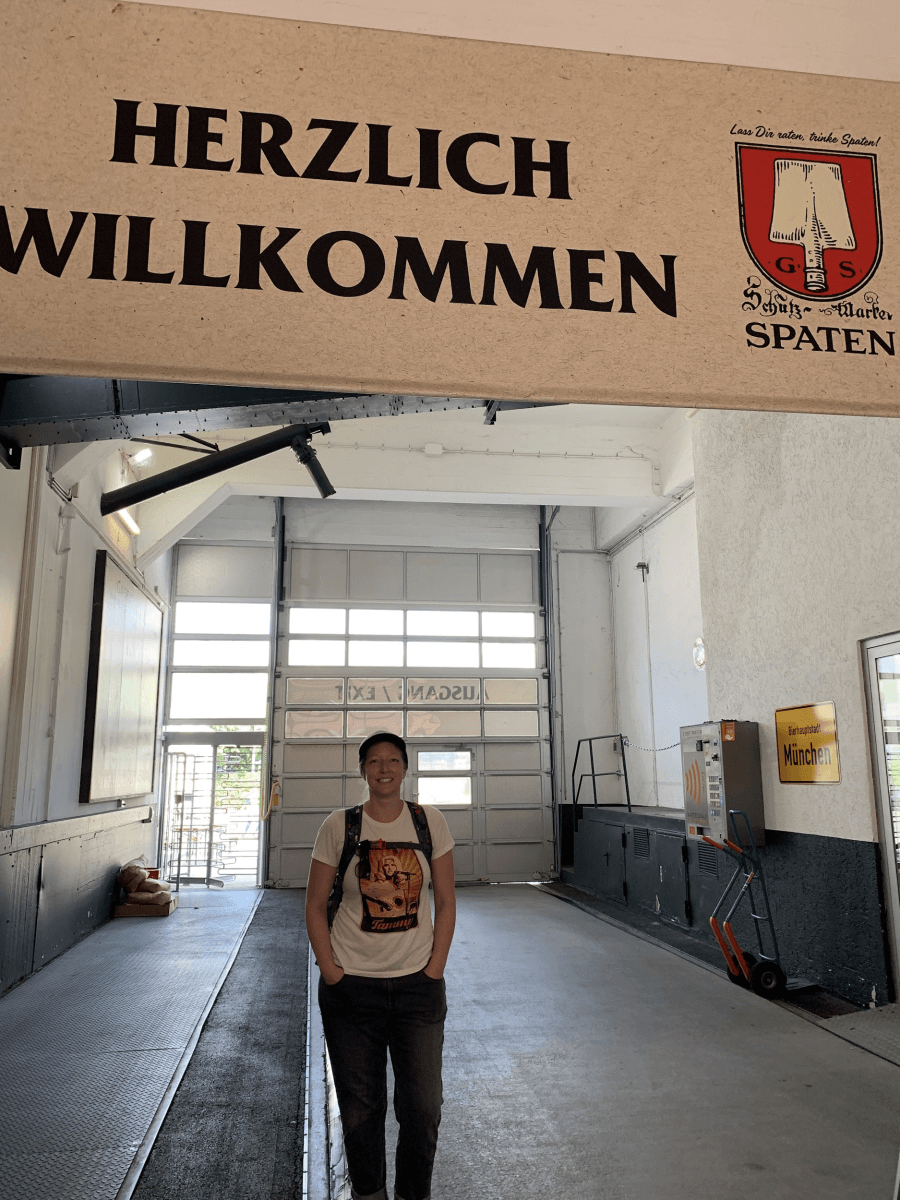

Our first planned group outing is a walk through the Viktualienmarkt in central Munich, as we make our way to Spaten and our official brewery tour. Having been established in 1397, Spaten is one of the six Munich breweries that is allowed to serve beer at Oktoberfest (the beer must be brewed within the city limits of Munich). Today, Spaten is integrated with Franziskaner (which only produces wheat beers) and Löwenbräu, another one of the six Oktoberfest breweries which started around 1383. As a unit, they are owned by AB InBev. Much like the history of beer and breweries, present day ownership is convoluted as well.

Spaten Brauerei, Munich, Germany

Spaten Brauerei is huge. Our tour guide is Denis, a young man who is studying brewing science. This seems to be a common theme with people we meet on our trip; beer is not just something they enjoy, it is their life. As this is our very first stop, we have many questions for Denis and he is pleasant and happy to share what he can. (Being part of AB InBev, there are some things we can’t really ask about or take pictures of). We see everything here; the brewhouse, the malt silos, the fermenters and cellar, the packaging facility, their own basement museum, and of course the very special rooftop bar at the end of the tour where we are served pretzels the size of our head and some sort of meat slab that I did not partake in. (Look for my future essay on being a vegetarian in Germany). This special bar, at the very top of the tower in what used to be the old malt house, gave us an amazing view of Munich, and of course we were encouraged to try every beer that was available. At one point I ask Denis about one of my favorite Spaten beers, Optimator, which is a doppelbock. He’s never heard of it. I’m absolutely baffled and start Googling it to show him, and what I learn is that some of their beers are for export only. Who knew? One tidbit that I still think about is that Spaten produces so much beer that during the busy summer season, they package 24 hours a day, days a week. In the ‘slower’ seasons, it drops to 5 days a week.

After a wonderful start to our journey, we head to the Augustiner Biergarten, where we have dinner reservations. Augustiner is also one of the main six Munich breweries, and they have more than one Biergarten, but we are visiting their largest. Again, the weather is beautiful, it’s late afternoon, and the outdoor seating is full of people enjoying their beer. One of my favorite things is a small truck that cruises around and picks up empty beer mugs. The outdoor area offers food and beer, and it’s basically self-serve. So we walk up to the counter and grab a half liter of whatever is there. Sometimes you want a radler (half beer, half lemonade), but that particular keg isn’t tapped at the moment. This isn’t a situation where you order from a tap list; you take what’s available and smile. I’m finding at this point that no matter where we seem to go, there is a limited beer selection. The menu typically consists of a helles, a dunkel, a radler, a weißbier, and maybe one or two other options. For those of us used to craft breweries with 20+ taps and flights and barrel aged this and milkshake that, it can be strange to have such limited choices, but I actually appreciated it. Do I want something light? Helles. Dark? Dunkel. Different? Wheat beer. Light and fruity? A radler. It made ordering easy because there was no analysis paralysis, and over the course of our trip we tried the helles or the dunkel from each region and we could compare and contrast them.

Helles yes, Augustiner Brewery, Munich

Our dinner experience at Augustiner is nothing short of exciting, and not just because of the delicious beer and food we enjoyed. Before we’re seated, Trip takes us on a quick tour of the seating downstairs in the basement. It’s a huge stone room that functions as extra seating, but it was also used as a bomb shelter during WWII. It’s strange to imagine people huddled down here while bombs were dropping, especially with the bar in the corner, but it’s another reminder of how intertwined beer is with the history of this city. It’s a beautiful evening, so the tables outdoors are full, which means that even though we have a reservation, there’s no space for us. Instead, we’re seated inside at a large table in an empty room. Apparently we are at the “locals” table, which is normally reserved for local regulars, but they’re all outside right now. Somewhat quickly however, the weather changes and we are suddenly dealing with a huge thunderstorm. People come rushing inside out of the rain, and we are booted from our table because the regulars have returned to claim their spot. It’s tradition.

Our second day starts bright and early with lots of transit confusion and delays, but eventually we are on our way out of the city and into hop country. There are four main hop growing regions in Germany; Hallertau, Tettnang, Spalt, and Elbe-Saale. Three of these regions are in Bavaria, and we are going to visit all three of them. As a hop-head, I am beside myself with anticipation. If you’ve never been to a hop farm during harvest, it’s difficult to describe the magic and the excitement and the fields of green and the AROMAS. I am looking forward to meeting the people that work in this centuries old industry.

The first people we meet are Carlos Ruiz, Chief Sales Officer, and Johann Pichlmaier, CEO of HVG Hallertau in Wolnzach. “HVG” stands for Hopfenverwertungsgenossenschaft (clearly), which translates to Hop Processing Cooperative. The cooperative, which works with and represents hop growers in the Hallertau region, was started around 70 years ago, but hops have been grown here since the 700’s. At the time HVG was created, there were around 10,000 farms growing hops, and today that number has sadly dropped to about 841 farms. It is still the largest hop growing region in Germany. Carlos and Johann tell us that worldwide, there are around 2,000 families that grow hops, but 1,041 of those families are in Germany. These farms, and HVG Hallertau, export around 80% of what they grow. With the explosion of craft lagers in the past few years, there has been a demand for German hops so that these beers can be brewed to style. Some varieties that many of us are familiar with include Hallertau Mittelfrüh, Herkules, Hallertau Tradition (it’s tradition!), German Saaz, Perle, Magnum, Huell Melon, Hersbrucker, and Mandarina Bavaria. One thing I find fascinating is that the German government is leaning on hop growers to be more water conscious and reduce the use of chemicals and pesticides. Drip irrigation is a recurring theme that we will talk about on this trip, and how to reduce the use of groundwater. Interestingly, some countries, like Japan, have very strict import requirements on hops, so random samples are taken throughout the harvest and production process and tested for at least 500 different chemical compounds. Any time a hop cone changes shape or is packaged/re-packaged, it gets an updated provenance document. Basically, each individual pellet can theoretically be traced back to its initial bine if needed.

A beautiful, fresh hop cone with all of its aromatic lupulin beads.

Having a discussion about the state of the hop industry is definitely interesting, but we are excited to get out into the fields. We are treated to lunch by Carlos and Johann, as well as Erich Lehmair, the incoming CEO as Herr Pichlmaier is retiring. We are at a small, local gasthaus where the owner makes his own sausage and mustard, of course. I eat the first of many, MANY käsespaetzles. The weather is beautiful and we are of course trying more local beer. Today we are having beer from Hofbrauhaus, which is a different Hofbrauhas. Sometimes it’s thought to keep everything straight, especially when you’re a tiny bit tipsy. One thing I notice, and wholeheartedly appreciate, is the team from HVG talk to us Pink Booters like equals. They want to know our opinion of what’s happening in the beer industry where we live, and if we have any suggestions for them, about anything. As a woman in the fermented beverage industry, I can say that this is not something I’m used to. They acknowledge us as capable, intelligent brewers, and they value our thoughts.

After lunch, we head to our first hop farm, which is great as we are already full of heavy food and beer, and hops have been used for centuries to induce sleep. Let’s do this. We meet with Andi Widmann, who is very young, but already a second (or third?) generation grower. He has a large facility in the countryside, and it’s truly a family affair. His parents are still involved and his sister is running the baling machine. Immediately I can see that this is where the Germans and Americans differ in their manner. Just that morning, which was the first day of harvest, Andi’s harvester (the machine that drives up and down the rows of bines and strips them into a truck) had broken down, so stress levels were a bit high. But he greeted us with smiles, and took hours out of his day to give us a tour of his facility, a ride out to the fields, and share some beers. When we drove out to the fields, he asked if we wanted to just jump in the back of the truck and hold on. We made the short ride and watched as the machine did its work moving up and down the rows. We even got to try what it used to be like pulling the bines down by hand, which was not easy. Then we all hopped back into the truck on top of the most beautiful bed of hops. No PPE, no signing a waiver, no safety lesson first. Just an assumption that we are all adults and have common sense. We are definitely not in Yakima anymore, Dorothy.

Our group (minus Brad) at the Widmann Family Farm near Wolnzach, Germany.

After a busy day of learning, eating, drinking, and helping with harvest, we of course need to have another drink. Trip has arranged for us to visit the home of Christian Zehetmaier, a local home brewer. But homebrewer is an understatement. Christian has a pretty large brewhouse, set up in a gravity style over three levels.He has his own walk-in cooler. His beers are on tap. And there are about 15 locals outside in his little Biergarten that come to hang out and drink. The set-up is pay what you want. As we sit there, I just think wow, this is the most amazing place ever. Not just Zehetmaier’s, but Hallertau and Bavaria. No one speaks English, really, so we stumble through pleasantries and enjoy our beer. We see a man wearing an Lfl/Gfh jacket, which is the research center we will be visiting tomorrow. He speaks a little English, and we learn his name is Anton Lutz. He’s a hop breeder who created Hallertau Blanc, Huell Melon, Callista, Mandarina Bavaria, and Ariana. When I get home a few weeks later I discover that he’s been written about in the quintessential Hops book by Stan Hieronymus. To me, he’s hop royalty, but here, he’s seemingly just a local guy that works in the industry and hangs out at Zehetmaier’s.

The next morning, after we eat breakfast at what has to be the cutest little B&B, we are off to LfL/GfH in Hüll. More acronyms, which stand for Bayerische Landesanstalt für Landwirtschaft (the Bavarian State Research Center for Agriculture) and Gesellschaft für Hopfenforschung (the Society for Hop Research). We are greeted by Sebastian Gresset who is the Director of the Research Center. This facility, established in 1926, is where they are actually doing the research and the breeding of new varieties. Much of their funding comes from government and public agencies. We learned earlier that there is a push to employ less pesticides in hop farming, so chemical and pesticide companies no longer have any interest in the industry, which means these hop consortiums now have to do their own research. One thing that seems to be promising is integrated pest management, or beneficial pests, and I find it super fascinating that between harvests, wine grapes are planted in between the empty rows to give these friendly pests somewhere to live. Sebastian also tells us that in 1970, their most popular of seven varieties were Mittelfrüh, Northern Brewer, Hersbrucker, and Brewer’s Gold, but now, there are 42 varieties, a lot of which were created to cater to the American market who wanted all these fun, new high alpha acid hops for their IPAs. In order to support this research, a lab facility is definitely needed, and we get to meet the Lab Director, Klaus Kammhuber. He reminds me of an adorable grandpa who wants to show us all his hop grand babies. We are awestruck at the fancy, top notch (mostly Anton Paar) equipment he has. Most pieces cost more money than I make in a year. Or five years. It’s exciting to know though, that there is such a detailed level of research and analysis that goes into hop breeding, all for our little beer making business.

Titan hops at the Hüll Hop Research Center

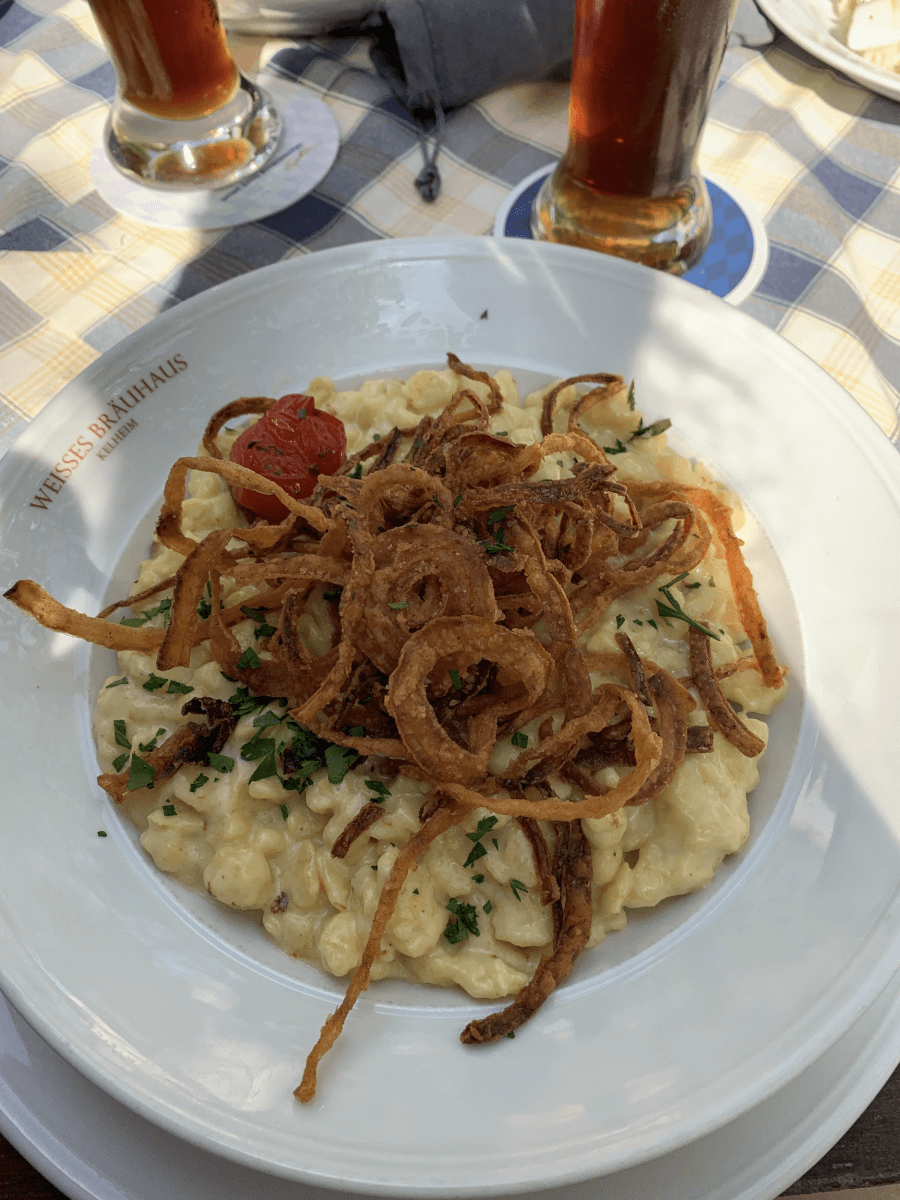

After more beer tasting at the Hüll Research Center Bar, we load up in the van to drive to Kelheim, which is the home of Schneiderweisse Brewery. G. Schneider and Sohn was originally a brewery located in Munich, but after the facility was destroyed during WWII, they decided that staying in Kelheim would be just fine for them. Their bier hall and biergarten are beautiful, but I admit I’m not terribly excited about this visit. Schneiderweisse, as you might guess from their name, specializes in wheat beers. These are not my preferred style of beer and I actually avoid them. In fact, most of us in our little group agree that wheat beers aren’t our favorite. But then we meet Günter Uhl, Production Manager, and Josef Lechner, the braumeister. Günter is one of the sweetest humans I think I have ever come across, and because we were delayed in our arrival, we decide to have lunch first and then do our tour. Which means more käsespaetzle for me (the best I ended up having on the entire trip), and meat legs the size of a basketball for others. Günter and Josef ask the server to bring a bottle of every type of beer they make to the table. It’s…a lot. Maybe ten different styles? I do perk up a bit because I see their Aventinus Eisbock, which I’ve had before and I do really enjoy it. It’s the only Eisbock available in Canada and it’s wonderful. As we eat and chat, it’s clear that Günter and Josef are very fun and laid back, and it seems that some of that stems from the fact that they are not held to the Reinheitsgebot at Schneiderweisse, for one because most of their beers are wheat ales which did not originally fall under allowed brewing ingredients, but they also seem to recognize that his Purity Law can be a bit unnecessarily extreme. I’m glad they feel this way, because they have made some amazing beers, and my new favorite beer of the trip is their Hopfenweisse, a dry hopped wheat collab with Brooklyn Brewery. I am also still a bit tipsy and gushing about the Aventinus Doppelbock and the Aventinus Eisbock, so Günter orders me another glass on draft. This is the best day ever, and we haven’t even seen the brewery yet.

Käsespaetzle at Schneider Brauhaus

As a brewer, my preference is for ales, for many reasons, so seeing the brewery at Schneiderweisse is amazing. We are taken into the primary fermentation area, which is typically not open to tours, because the entire room is full of open fermenters. Yes, open fermentation! We get to see these little fellas bubbling away, and the smell is amazing. I’m surprised that none of us dropped our phones in the tank while taking pictures. We learn how the yeast is harvested and sent to a steel tank to be repitched in future batches. We get to see the area where the alcohol is stripped for their alkoholfrei beer, which is becoming very popular in Germany and Europe. It’s fascinating because the basic concept is that beer is run through a machine that removes the ethanol (and a computer monitor shows the ABV dropping in real time), but where does that ethanol go? Somewhere. The government has secured the piping so that it can’t be tampered with in case someone wanted to siphon off that straight alcohol. We also see the Eisbock room, which is where they freeze their Aventinus Doppelbock to remove water and boost the ABV to 11.9%. I love this room. Like most historic breweries, they also have a mini museum and here we learn about Mathilde Schneider, wife of Georg Schneider III. He died young, so she took over the brewery but as a woman in her day, she couldn’t actually fulfil this role publicly, so she had to make decisions behind the scenes. She led the brewery through the trauma of WWI and it grew to be the largest wheat brewery in the country. She was also the creative force behind the Aventinus Doppelbock. She died in 1972, so we aren’t talking ancient history here. She is my new beer hero. Every. Brewer should learn about her.

Fluffy, pillowy weißbier krausen

Günter shows us their lab. We have seen, and will see, a lot of laboratories on this trip, and true to their German culture, they are immaculate. If it’s end of the day, everything is clean and organized and ready to go for the next day. A place for everything and everything in its place. I’m gobsmacked, especially when I think about some of the production facilities I’ve worked at and how sweeping or mopping was only done on a special occasion. We get to see their special beer cave where they keep limited and aged beers, and Günter gives us all something to take home. I actually ended up with two, both barrel aged, cuvée, and I will probably save them until I’m on my deathbed.

We end this day with a visit to a Volksfest in Freising. Think Oktoberfest, but smaller. But not really that much smaller. The beer tent is huge, and finding a seat is difficult. A couple of lovely young ladies let us sit with them, and then we go about ordering. It’s chaos. Once you flag down a server, you’d absolutely better be ready with your order and cash in hand. Just like you see on TV, these trained servers carry up to ten Maß mugs with just two hands. To do some quick math for you, a Maß mug can hold one liter of beer. One liter of beer weighs one kilogram, and one kilogram is 2.2 pounds. That means ten mugs weigh over 20 pounds. While I thoroughly enjoy the beer (as a group we tried something called a Geissenmass; dunkel beer mixed with cola and cherry liqueur), the enormous pretzels, and dancing to the some of the classics (Doris Day and ABBA anyone?), I realize that I now have no desire to attend Oktoberfest. The sheer size of everything is intimidating and I’m glad that Trip took us to a smaller version.

At this point, it’s hard to believe that we are only about halfway through our beer and hop journey. We have done so much, eaten so much, drunk so much, and met so many wonderful people that it’s strange to think that we still have another four days or so. But also exciting, because our next stop is Tettnang. THE Tettnang!

In my head, I’ve built up some of these hop regions to be famous and historic, so I assume that they will have beautifully appointed offices. So when we roll up to HVG Tettnang, it’s surprising that they have kind of a tiny office space, and a somewhat small warehouse area. But, in this region, there are only 124 growers, so it makes sense. We meet with Jürgen Weishaupt, the general manager, and the father of Denis, our tour guide at Spaten. It really is a family industry. We hear a lot of the same info from Jürgen as we’ve heard other places, like 2022 and 2023 were terrible harvest years due to drought, 2024 looks good, but production is down and back stock is piling up. No one really seems to know where the industry is going, but everyone is anxious. Brewers won’t use more hops because they’re cheaper; their recipes don’t change.

After our brief time at HVG (it is Saturday after all), we stop at the liquor store right next door and I’m eagerly grabbing anything that looks interesting. You can find quality beer in a flip-top bottle that costs less than 1 Euro. I also buy a bottle of hop infused oil, because, when in Rome. It will be a fun tasting adventure when I try it with the 56% ABV hop schnapps I bought at our last guesthouse.

Lunch is at a beautiful restaurant called Max and Moritz, which overlooks a vineyard. Their beer is passable, but we are mainly there for the beer and the food, which do not disappoint. I share a dish of potatoes glazed with malt foam (and more käsespaetzle), and I think about how much beer is incorporated into daily life here. We’ve seen hop garlands and crowns for sale in various markets, or signs at farms advertising hopfenpflanzen, or hop plants for sale. You can buy them almost anywhere. And drinking beer is seen as an enjoyable pastime, and it’s not at all unusual to see entire families with children at a Biergarten. Patrons aren’t rushed out either. There were times before our tour started when I planted myself at a table somewhere and worked on my crossword. It’s such a different way of life, and I think North Americans are missing out. As we leave Max and Moritz, we drive through a vineyard and we see a group eating their picnic at a table that’s set up in the field, for anyone to use.

Our next stop is Hopfengut, a craft brewery/working hop farm/museum. Hopfengut is a family owned business, and when we arrive, harvest is in full swing, and there’s also a wedding taking place. It’s a stunning setup, and midway through the museum tour, we walk out onto an overlook that takes us right into the hop bines. We’ve met one of the owners, Lukas Locher,whose family has been in the hop business for generations, and as he is ridiculously busy on this Saturday, he leaves us with Christina who acts as a tour guide and educator. She takes us throughout the facility, and we discuss the role of women in brewing and hop picking. We even see the hopfensau replica in their museum. Yes, the hop sow, or hop pig, represents the female picker who picks the final hop of each harvest. The idea is noble, but I don’t think we ever learned why she’s depicted as a sow. In any case, Christina tells us about Hopfengut beer. and how they only brew three varieties; a lager, an IPA, and a dark lager. We try them all and they are unbelievably good. Maybe we are just biased toward anything “craft” and not macro. The four of us Pink Booters have been having such a great experience that we tell Christina that she should join Pink Boots because she’s a perfect candidate. And she does, that night. This is absolutely what PBS is about, and why it’s such a great organization.

After another full day of drinking and learning, we need to eat. Trip has made reservations for us at Tettnanger Krone Gasthof, followed by a brewery tour. They brew their own beer, so of course we all try a different brew. I ordered nudeln, which is just a different shape of cheesy noodles. After dinner, I’m surprised to learn that the brewer and main chef, Fritz Tauscher, is the same person. Their guesthouse is also an inn. How does he have time? He takes us to the brewery and this is a unique experience. He tells us that after boiling the wort, the beer travels up to the roof of an adjacent building before coming back down to the fermenter. He said they used to have a cool ship, but that’s been gone for a long time. I asked why it still goes all the way up before coming down again and he said, “that’s just how we do it.” We are also in town the day before the “Bähnlesfest”, which is an annual festival that commemorates when the train stopped coming to town. This also is strange to us, but as Fritz explains, this is just how they do things. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it, but German style. In general though, after seeing the many lager tanks two levels below ground, the huge storage fridge, and the massive bottling line, it’s hard to believe that this is mostly just a one man show. It’s likely that title of head brewer will be passed down to one of Fritz’s children, just as he took over for his uncle, and planning ahead, both of his children have names that begin with “F” so that the F. Tauscher in the name doesn’t have to be changed. Genius.

A Helles lager from Tettnanger Kronenbrauerei

We’re made it to Sunday at this point, although it has felt like a month instead of just a few days. In Germany, and basically most of Europe, everything is closed on a Sunday. Because of this, there’s not much we can really do aside from sightsee, and drink beer. Trip has planned a pretty cool adventure fr us, which includes four beers in four countries in one day. We take a ferry from Friedrichshafen in Germany across Lake Konstanz to Romanshorn, Switzerland. We each order a beer on the ferry and I’m pleased to see that the server in the tiny cafe makes sure that we have the appropriate glass for each beer we order. Proper glassware, it’s tradition. After a few hours in Switzerland, we drive towards Liechtenstein. Unfortunately, weather and other delays mean we won’t make it to Liechtenstein, but we do stop at the border of Austria and Germany to take photos. There are no booths or tolls or border agents. Just a river. For us North Americans, it’s bizarre. We then spend a few hours in Austria on the lake, and even though it’s sprinkling, it’s beautiful. I will never get used to buying a beer, or RTD, and then walking around with it in public. Or taking it on a bus or train. It just makes so much sense. It’s just a drink. We say goodbye to Austria and head back to Germany, where we spend much of our day in Lindau, which is a neat little island. There’s a lot to see in terms of architecture, shopping, eating and drinking, and there’s even a pop-up artisan market. We end the day with dinner at an Italian restaurant, run by Polish people, serving our motley little crew. Our server said she never would have expected this random situation to have presented itself, but here we are, and it’s another reason I love Europe. The diversity is welcoming and wonderful.

It’s Monday and we’re back in school as we get ready for our tour of IREKS Malting in Kulmbach. I think I was the only one who had heard of IREKS before, because they used to distribute in Canada, but as I learned, their only supplier had recently gone out of business so they did not have any representation in North America any longer. Our guide for the day, Robert Sprinzl, is the International Export Director. As he tells us more about the history and current operations of IREKS, I feel sad for the brewing side of the company. It was started in 1856 in Franconia, by a brewer and a baker. Their main product was malt, but during and after WWII, malt was not allowed to be used for brewing beer, so the baking side of the company grew. To illustrate this, Robert tells us that there are 3,000 employees at IREKS, but only 160 work on the malting side. What? How can that be? We take another laboratory tour and it is state of the art with the latest technology, and then Robert tells us that this is the BAKERY lab. The brewery lab is much more dismal with outdated (yet functional) equipment. He says that if they need really accurate data on malt products, they send it over to the bakery lab. As a brewer, I’m a bit offended, but I also love based goods, so I’m torn.

In general though, the IREKS facility is massive, and overwhelming. They produce malt for brewing, flour and other baking mixes, spices and spice blends, and a malt extract. They’re capable of producing gluten free, kosher, and halal grain. We get to help put together a spice blend using their intricate computer system, and Robert shows us where and how they produce malt extract. But, as with most things here, the malt extract is only sold to bakers. It’s clear that the baking side is supporting the brewing side, and I decide I’m going to make it my personal mission to spread the word of IREKS to fellow brewers when I get home. After all, their conference rooms are named after types of malt; how cool is that?

Robert takes us out to dinner, along with Stefan Bergler, who is the President of IREKS. We’re eating at a small, local restaurant which seems to be our thing now. Because we are in Kulmbach, and there is a huge Kulmbacher Brewery right up the road, we are all drinking Kulmbacher. Again, I’m thinking about how this really is a once in a lifetime experience. There are the macro brews that most of us have heard of and have access to where we live, like Paulaner, or Bitburger, but I’ve never heard of Kulmbacher. Or Tettnanger Krone. Or Farny. We can only try these beers in Germany and I make a point at every meal to try something local.

We’ve made it to our last day of the trip, but we have quite a full day ahead of us. We’re driving to Spalt, the last hop region on our to-visit list. It’s the second smallest region with only 44 growers. Again, it’s hard to imagine that this tiny region of just a handful of family farms produces so many hops. The head of HVG Spalt is Dr. Frank Braun, and he is a trip. He’s excited and passionate and extremely smart. He shows us the small hop farm they have on site, to produce some experimental cultivars, and we see the huge refrigerated storage facility as well. It’s mesmerizing, but also a bit sad as he tells us that the hop industry in Germany has had some rough years recently. He has pallets upon pallets of hops from previous harvest years, which are nitrogen flushed and stored cold, so they’re perfectly good for brewing. But who wants to buy “older” hops when they can get fresh hops for almost the same price? And then what happens to all these hops if they’re not sold? It really is depressing to think about, and yet, hops are so synonymous with beer that no one has really come up with other uses for them.

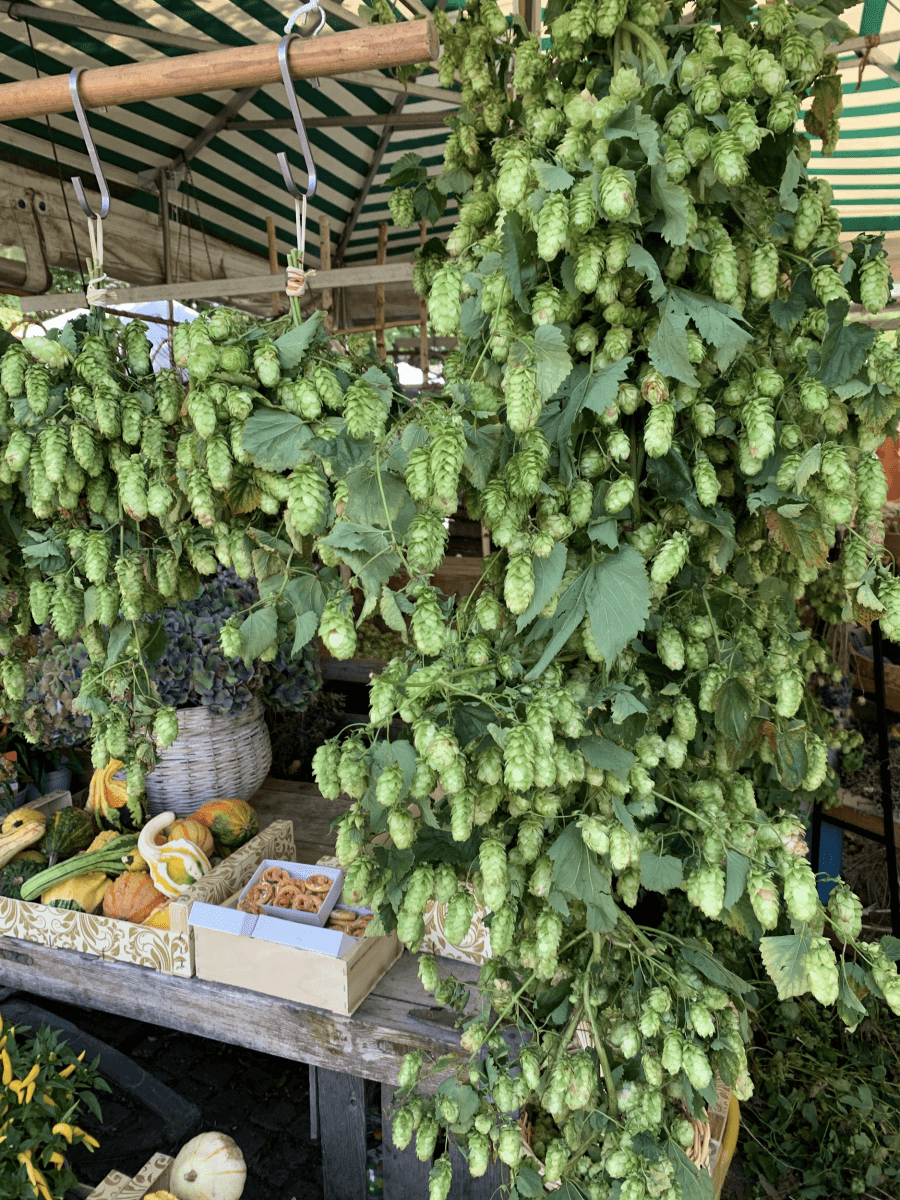

Hop bines for sale at the farmer’s market

We have lunch with Dr. Frank, and as we walk back to the car, he steers us to a house about half a block away that’s in the middle of processing hops. This is a multigenerational farm, and they know Frank of course because aside from him, there’s maybe only one other person who works at HVG Spalt. This family, which includes son, mom and dad, and grandma, gives us an impromptu tour of their facility. It’s very old school, and so neat to see happening right in town. They bring hops in from their farm on the outskirts and process things here. And of course, they are extremely friendly and welcoming and don’t seem to mind taking time out of their busy afternoon to show us around.

After this last hop “farm” visit, we’re on our way to our last official tour, at Stadtbrauerei Spalt. This translates to Spalt City Brewery and although this variation of the brewery was established in 1879, the brewing industry in Spalt can be traced back to 1376. The unique thing about this particular brewery is that it is owned and managed by the city. So technically, the mayor, or bürgermeister, is the boss. Which I think means that you can vote for your own boss? In any case, we are getting a tour from Stefan Herz, who is the braumeister. This place is absolutely enormous, and the architecture is very old. But again, like every other place we’ve seen on this trip, it’s immaculate. Clean, clean, clean. The mash tun looks brand new. It really is amazing how detailed these workers are when it comes to cleaning and sanitation. On the day that we’re there we get to see the filtration process, and then of course, we end with the obligatory beer tasting. To just reiterate how much the Germans love their Helles, I asked for a bottle of dunkel and Stefan brought me a couple of warm ones. He said that none of the employees drink dark beer, so they don’t keep it in the fridge. But I don’t mind because now I can take it home with me.

Our last supper is going to be at the famed Weihenstephan brewery back in Munich. It’s in a stunning location with a great view, and even though the Biergarten outside is closed, the inside is just as beautiful, full of arched stone ceilings. We are meeting our last special guest of the trip, Sebastian Hohentanner who is German but lives in Japan and represents IREKS and Spalt Hops there. After looking at the menu, we’re ready to order our first beer, but Sebastian says no, we all have to order the Helles. He said that’s how it is; you just sit down and order a Helles which gives you time to think about what you want next. So, it’s tradition and we cannot argue with that. I order my last round of käsespaetzle and as a group we share some obatzda which I’ve been wanting to try. At one point I want to try the Doppelbock, but Sebastian and the male waiter want to make sure I know what I’m doing, since it’s a 7% beer. I tell them yes, this is kind of like a starter beer back in the US, but considering most German beers are 5% or less, it makes sense that they want me to be sure. The idea here again is not to get plastered, but to enjoy the time with friends and family over the course of a few hours. There’s no rushing here, which is nice, because I really don’t want to leave this place or these people. It has honestly been one of the best experiences of my life, and I feel that nothing I write will adequately do it justice.

So I will end with saying thank you Trip, and thank you Pink Boots, for this once in a lifetime opportunity. Prost (with eye contact)!

Our final dinner at the oldest continuously operating brewery in the world, Weihenstephan in Munich.